July 29, 2019

by Mark Traphagen / July 29, 2019

by Mark Traphagen / July 29, 2019

Google Analytics is probably one of Google’s greatest gifts to the marketing world (second only to the search engine that bears its name).

The free version is incredibly powerful and available to anyone with a website. Armed with Google Analytics, any webmaster, SEO, or internet marketer can gain powerful, actionable insights for traffic growth, measuring advertising effectiveness, audience nurturing, and bottom-line-enhancing ROI.

However, as with any complex tool, it’s all too easy to misunderstand or misuse the information it provides. Users need to know not only where to look for the data they need but also understand what it means.

Let’s look at a few common misunderstandings about Google Analytics. Our goal will be to have more confidence in what this tool is actually telling us so that we can make accurate, well-informed marketing decisions.

Several years ago, Google changed the names of many of the standard reports, dimensions, and metrics in Google Analytics. Though the changes might have seemed confusing at first, they were made primarily to better reflect the way Analytics works.

A prime example of this is the concept of “sessions.” Prior to the update, Google Analytics called this metric “visits”. That name implied that Google was measuring the amount of times a user visited the site, regardless of the amount of time spent on that site. However, that is not how Analytics measures the presence of a visitor on your site.

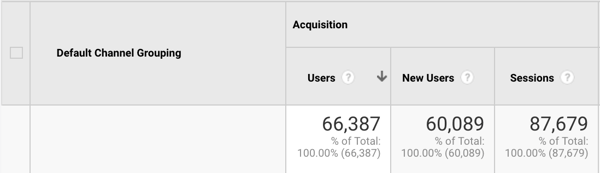

The Sessions metric is found in many Google Analytics reports. Here, we see it in the Channels report in the Acquisition section:

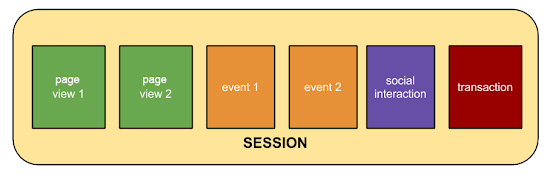

Google defines a session as “a group of user interactions with your website that take place within a given time frame.” Google goes on to say that a session could be thought of as the container for the actions a user takes on your website. Below are examples of some of those actions:

Source: Google

Source: Google

The default session time frame is 30 minutes. The first interaction a user has with the site (such as clicking a link, navigating to another page, or making a transaction) marks the beginning of the 30-minute minimum session. If that user does not make another interaction within 30 minutes, the session ends regardless of whether or not the user still has the site open on their browser.

So what happens if the user does nothing for more than 30 minutes, and then takes another action? In that case, when the user takes the new action, a new session starts. Thus, any one user could have multiple sessions during one visit (visit = one instance of opening your site on a tab in a browser and leaving it open).

If you think about it, time-limited sessions make more sense than measuring visits. A visit is too amorphous to be meaningful. A user could open your site in a browser, do a few things, and then go off to do something else, leaving your site open in a tab or window. When that user returns later, they might pursue an entirely different intention on your site.

A session measures a distinct “chunk” of interactions by a user, more likely to be tied together in a single chain of intentions. Therefore, a session tells you a lot more about an actual user’s “story” on your site: how (and perhaps why) they went from one action to the next.

Google promotes the concept of “micro-moments,” the dozens of small inquiries and encounters that contribute to a decision to purchase in the digital world. Though Google’s micro-moments take place anywhere in the digital universe, you should think about the micro-moments on your site as well.

Ask yourself what visitors tend to do in each session. Where do they begin and what do they do after arriving? How well are you guiding them along a chain of micro-moment interactions that will lead them to the action you want them to take?

Another now-obsolete metric name that we still tend to hear is “time on site.” By this, most people mean the amount of time a user stays on your page once they arrive. It used to be assumed that the longer someone remains on your site, the better.

That isn’t necessarily true.

Many users may not actually be “on” your site for the entire time they have it open in their browsers. Oftentimes, users leave multiple tabs open on their browsers. It could be likely that the majority of the time your site is open in a tab, the user isn’t spending their time looking at it.

This is another reason why Google switched from “visits” to “sessions” as a key metric in Google Analytics. Sessions only remain active while a user is interacting with your site, making them a much more useful metric than “visits”.

Google Analytics now uses Average Session Duration and Average Time on Page metrics, but they are not the same thing.

Average session duration is shown primarily in the Acquisitions reports of Google Analytics, representing the average length of time of user sessions.

Average time on page shows itself primarily in the Behavior reports of Google Analytics. It is the average length of time a user is present on a particular page on your site.

To simplify, “session duration” has to do with active time on an entire website, whereas “time on page” has to do with only a particular page on the site.

| NOTE: The “time on page” metric only records time for users that go to more than one page on your site during a session. |

When a user lands on a page on your site from a search engine, Google Analytics starts a timer. The “stop” on that timer is only triggered by the action of loading a new page from the same website. So, if a user loads a page, stays on that page for 15 minutes, and then leaves your site without loading another page, their time on page is recorded as 0:00, not 15:00.

If another user lands on a page on your site from a search engine, then after 15 minutes navigates to a different page on that same site, Google Analytics will record a time on page of 15 minutes. The timer starts again for the new page, and just as before, will only record a time if the user loads a third page, and so on.

That has an important ramification for average time on page. That metric is the total recorded time divided by the number of page loads. All visits which resulted in 0:00 page time are also averaged in.

For example:

User 1 stays on page A for 15 minutes, then loads page B (recorded time on page 15:00)

User 2 does the same as User 1: stays on page A for 15 minutes, then loads page B (recorded time on page 15:00)

User 3 stays on page A for 15 minutes, then exits the site (recorded time on page 0:00)

The average time on page for this scenario would be 10:00 (30 minutes divided by three page loads).

The average sessions metric is used in acquisition reports because, in those reports, you’re primarily concerned with the overall site experience and usage of users, depending on where they came from (how they arrived on your site, whether from a search result, a social media link, an ad, directly entering your site address in a browser, etc.).

The longer the average session duration from a particular source, the more certain you can be that users coming from that source are having a useful and satisfactory experience on your site.

In this case, you can evaluate how effective your content and other pages are in satisfying users.

As a convenience, Google Analytics provides a set of default “channels” in the Acquisitions reports section. These channels correspond to the high level major sources of traffic to most sites. Here are the default channels:

Analytics uses predefined source information to determine to which channel bucket any incoming traffic should be assigned. Most of the time that works perfectly fine.

Most of the time.

When Google Analytics can’t accurately recognize the source of traffic, it often gets dumped into the “Other” channel. If you find that your Other channel is getting a significant part of your traffic, then it may be the case that you have more misattribution than you should be comfortable with.

As noted above, Google uses its own rules to attribute what channel a source belongs to. It assigns a source and medium to any individual incoming traffic. Then, each channel has particularly defined source-medium combinations that are attributed to that channel.

For example, sources such as Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn with the medium “referral” will be attributed to the Social channel.

A monkey wrench hits the works when traffic comes in with its own source and/or medium that Google Analytics doesn’t recognize. The most frequent cause of this is custom UTM tagging.

UTM tags are labels that can be attached to the end of a URL that allow analytics tools to categorize and sort traffic to provide more granular information than the default sources. While the categories for UTM tags are standardized (e.g., source, medium, campaign, etc.) the labels themselves can be anything.

Let’s say a site wants to be able to differentiate the effectiveness of traffic driven by its own social accounts from all other referrals from social networks. This company wants to know how much traffic comes from their own link posts on their Facebook page as opposed to traffic from links posted by others.

This business might add a custom source UTM tag of “company-social” to the links they post on Facebook. In their analytics, they could filter for that source to see traffic sent from just those links.

However, the Social default channel in Google Analytics will begin under-reporting social traffic. Google Analytics will not recognize the “company-social” source, therefore dumping all of that traffic into the “Other” channel.

The fix for this is to either create custom channels or to customize the existing channels. In the latter case, you could edit the default Social channel and add a rule that captures any traffic from source=company-social into that channel.

Alternatively, you could create a brand new custom channel called Company Social and capture the traffic there.

As mentioned earlier, Google Analytics is a force to be reckoned with. With that, it’s important that those who choose to use the tool truly understand what it’s capable of. There are more than three misconceptions about Google Analytics, but clearing them up one at a time makes for a more successful marketing experience.

Already a user of Google Analytics? Write a review and tell us what you think!

Mark Traphagen is Vice President of Content Strategy for Aimclear. He is a sought after speaker at conferences such as MozCon, PubCon, and SMX, and a featured writer for major online publications such as the Moz Blog, Search Engine Land, Marketing Land, and a VIP Columnist for Search Engine Journal. Of course, he also regularly publishes on the Aimclear blog as well.

Build your own UTM code campaign Use the following form by entering your URL and UTM...

.png) by G2

by G2

There was a time when marketing primarily consisted of guesswork and creativity. While...

by Atul Jindal

by Atul Jindal

Customers are a difficult breed to please.

by Ninisha Pradhan

by Ninisha Pradhan

Build your own UTM code campaign Use the following form by entering your URL and UTM...

.png) by G2

by G2

There was a time when marketing primarily consisted of guesswork and creativity. While...

by Atul Jindal

by Atul Jindal