May 26, 2020

by Kai Tomboc / May 26, 2020

by Kai Tomboc / May 26, 2020

Ancient storytellers already understood that pictures are worth a thousand words – from depictions of volcanic eruptions to abstract symbols painted on caves.

Fast forward to today, and infographics have skyrocketed in popularity.

In this article, we'll take a closer look at the history of infographics: its origins, evolution through the centuries, and what lies beyond. You'll also meet the people behind the transformation of infographics over time – persuading skeptical governments to communicating with extraterrestrials.

Grab your beverage of choice and let's trace the roots of infographic design up to the present.

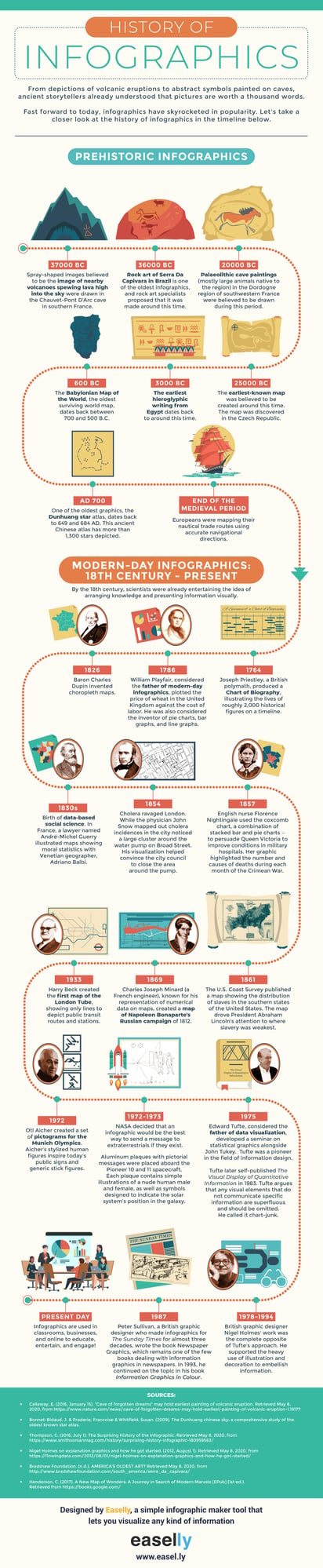

Talk about inception. Below you’ll find an infographic chock full of information about the historical timeline of infographics. We’ll break each of these sections down in more detail throughout the article.

Infographics can be traced back to the spray-shaped images in the Chauvet-Pont d’Arc Cave in France at around 37,000 BC. They were believed to be painted at around the same time as nearby volcanoes erupted and spewed lava into the sky.

Meanwhile, several rock art specialists proposed that the rock art of Serra Da Capivara in Brazil is one of the oldest infographics, dating as far back as 36,000 years ago.

Paleolithic cave paintings (mostly large animals native to the region) in Lascaux, around the Dordogne region of southwestern France, were believed to be around 20,000 years old. Apart from their age, these paintings were also famous for their size, sophistication, and exceptional quality. Many other decorated caves were found in the area since the beginning of the 20th century.

The beginnings of infographics aren't just limited to caves and rocks. Early adventurers and old school explorers also created maps, a not-so-distant cousin of infographics.

The earliest-known map representing a natural landscape was a rough representation discovered in the Czech Republic, dating back to 25,000 BC. Around 3000 BC, ancient Egyptians invented and used hieroglyphics to tell stories of life, romance, work, and religion. By 600 BC, the Babylonians were already using accurate surveying or triangulation techniques to create maps.

The Babylonian Map of the World, the oldest surviving world map, dates back between 700 and 500 BC. It's worth noting, however, that this map is a symbolic rather than a literal representation of Babylonia. Next to surveying the land around them, the ancients also turn to the skies above.

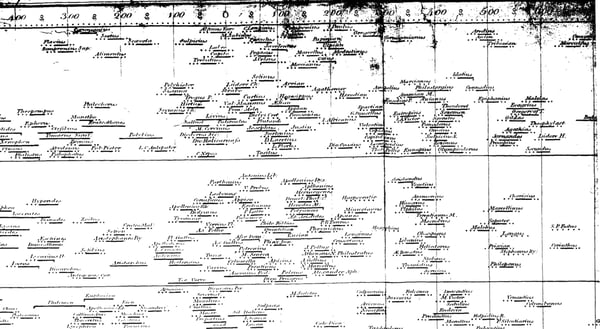

The Dunhuang star atlas is one of the oldest graphics ever found. It has more than 1,300 stars depicted and dates back to 649 and 684 AD.

The accuracy and graphic quality of the ancient Chinese Atlas lie in its superior visual quality (for its time) and accuracy. With its origins and real use unknown until now, the old astronomical document includes both bright and faint stars visible to the naked eye from north-central China.

By the 18th century, scientists and scholars were already warming to the idea of arranging knowledge visually.

British polymath Joseph Priestley produced what could be the predecessor of today's timeline infographics. It was called a "Chart of Biography," where the lives of about 2,000 historical names are plotted on a timeline. It covered figures from 1200 BC to 1800 AD and organized the historical personalities into six categories.

Joseph Priestley / Public domain

Joseph Priestley / Public domain

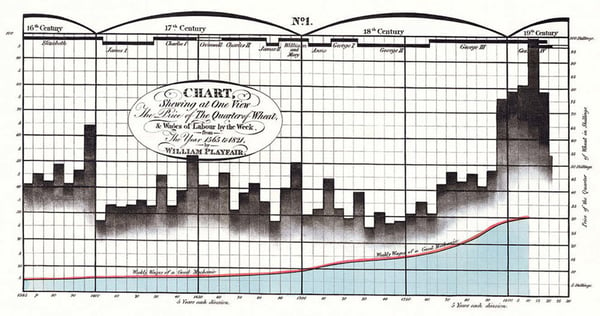

In the United Kingdom, people often complained about the high cost of wheat and claimed that wages were driving the price up. William Playfair, considered the father of modern-day infographics, wanted to find out if this was true by plotting the price of wheat against labor costs. Playfair's chart revealed that this wasn't true – wages were rising much more slowly than the cost of wheat.

Playfair’s Commercial and Political Atlas and Statistical Breviary. Cambridge University Press, 2005, 1801.

Playfair’s Commercial and Political Atlas and Statistical Breviary. Cambridge University Press, 2005, 1801.

According to psychologist Ian Spence who's writing a biography of Playfair, the father of modern-day infographics was ahead of his time. Playfair made charts because "For him, data should speak to the eyes and that the eye they were the best judge of proportion, being able to estimate it with more quickness and accuracy than any other of our organs."

Excellent data visualization, Playfair argued, "produces form and shape to a number of separate ideas, which are otherwise abstract and unconnected."

Playfair later published The Commercial and Political Atlas, which featured line graphs, bar charts, and histograms representing the England economy. In 1801, he followed this up with the first pie chart.

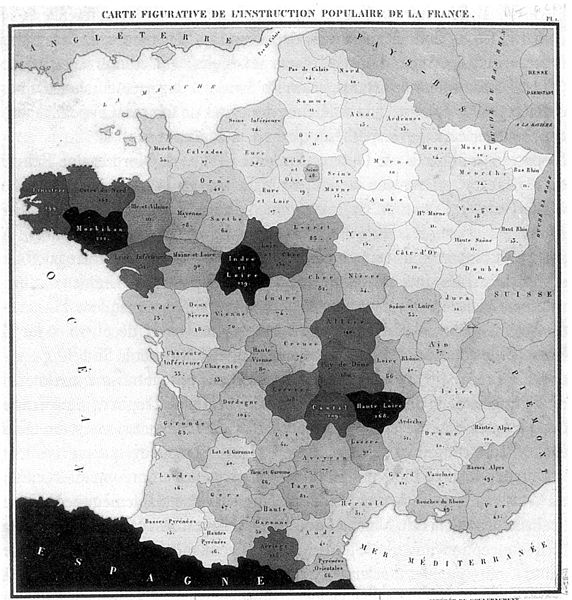

Baron Charles Dupin invented the choropleth map. A choropleth map has areas that are shaded or patterned in proportion to a statistical variable that represents an aggregate summary of a geographic characteristic within each region, such as population density or per-capita income.

Charles Dupin (1784-1873) / Public domain

Charles Dupin (1784-1873) / Public domain

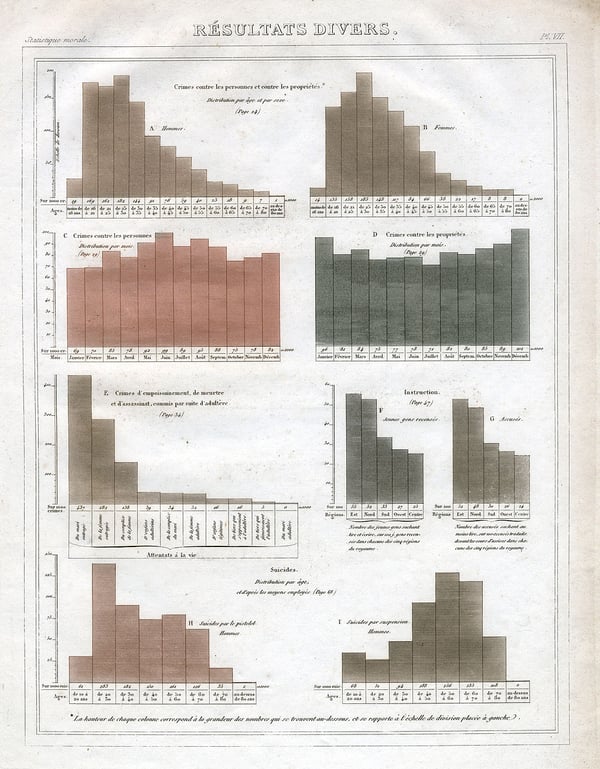

Data based social science was born In France, a lawyer named André-Michel Guerry created maps showing "moral statistics”. He was among the first to use maps with shadings to highlight data - say darker where illiteracy or crime was higher.

André-Michel Guerry / Public domain

André-Michel Guerry / Public domain

His work was controversial because it challenged conventional wisdom around that time. Social critics in France used to believe that illiteracy led to crime, but the lawyer's maps suggested otherwise.

While the physician John Snow mapped out cholera incidences when it hit London, he noticed a large cluster around the water pump on Broad Street. His visualization helped convince the skeptical city council to close the area around the pump. The epidemic subsided, and Snow's map helped nudge forward a crucial idea – diseases are caused by contact with an as-yet-unknown contagion (bacteria).

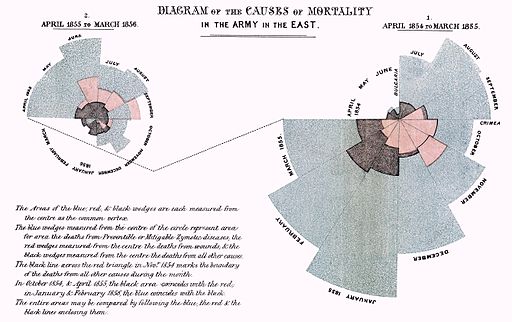

English nurse Florence Nightingale used a coxcomb chart (a combination of stacked bar and pie charts) to persuade Queen Victoria to improve conditions in military hospitals. Her graphic highlighted the number and causes of deaths during each month of the Crimean War: blue for preventable diseases in blue, red for wounds, and black for other causes.

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) / Public domain

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) / Public domain

The U.S. Coast Survey published a map showing the distribution of slaves in the southern states of the United States. The map drove President Abraham Lincoln's attention to where slavery was weakest.

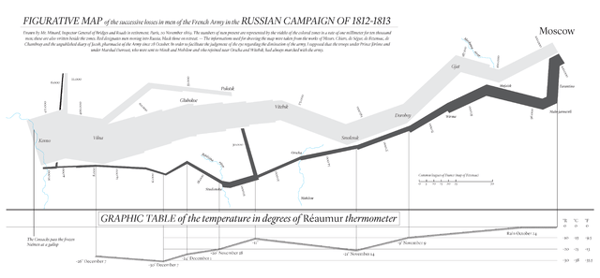

Charles Joseph Minard (a French engineer), known for his representation of numerical data on maps, created a map of Napoleon Bonaparte's Russian campaign of 1812.

Modern redrawing of Napoleon 1812 Russian campaign including a table of degrees in Celsius and Fahrenheit and translated to English.

Modern redrawing of Napoleon 1812 Russian campaign including a table of degrees in Celsius and Fahrenheit and translated to English.

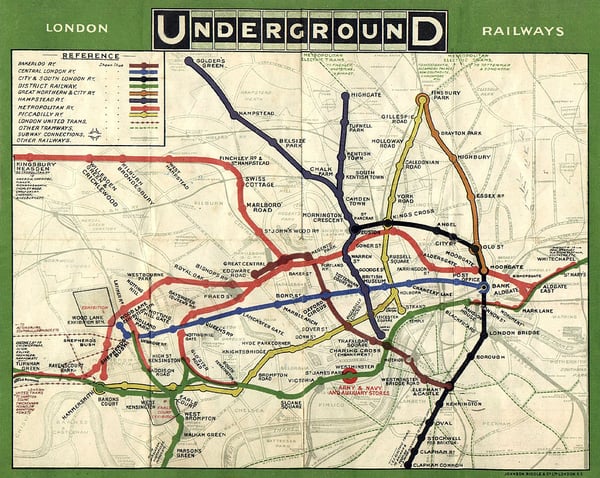

Harry Beck designed the first map of the London Tube. It showed lines to depict public transit routes and stations. This was a milestone in infographics graphics since it showed that visual diagrams could be used for everyday life.

Unknown author / Public domain

Unknown author / Public domain

Otl Aicher designed a set of pictograms for the Munich Olympics. Aicher's stylized human figures inspired today's public signs and generic stick figures.

Pictograms adopted to those of the Olympic Games 1972 in Munich, Germany symbolizing Curling, Figure Skating and Ice Hockey. Drawn by Otl Aicher, on Display at the Olympic Ice Rink.

Pictograms adopted to those of the Olympic Games 1972 in Munich, Germany symbolizing Curling, Figure Skating and Ice Hockey. Drawn by Otl Aicher, on Display at the Olympic Ice Rink.

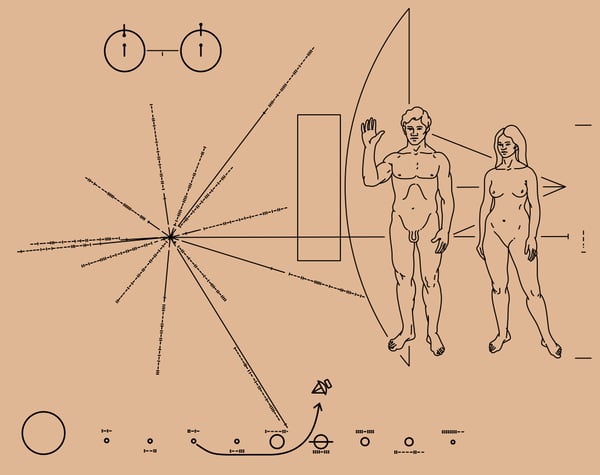

NASA decided that an infographic would be the best way to send a message to extraterrestrials if they exist.

Vectors by Oona Räisänen (Mysid); designed by Carl Sagan & Frank Drake; artwork by Linda Salzman Sagan / Public domain

Vectors by Oona Räisänen (Mysid); designed by Carl Sagan & Frank Drake; artwork by Linda Salzman Sagan / Public domain

Aluminum plaques with pictorial messages were placed aboard the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft. Each plaque contains simple illustrations of a nude human male and female, as well as symbols designed to indicate the solar system's position in the galaxy.

Edward Tufte, considered the father of data visualization, developed a seminar on statistical graphics alongside John Tukey, another pioneer in the field of information design. Tufte later self-published The Visual Display of Quantitative Information in 1983.

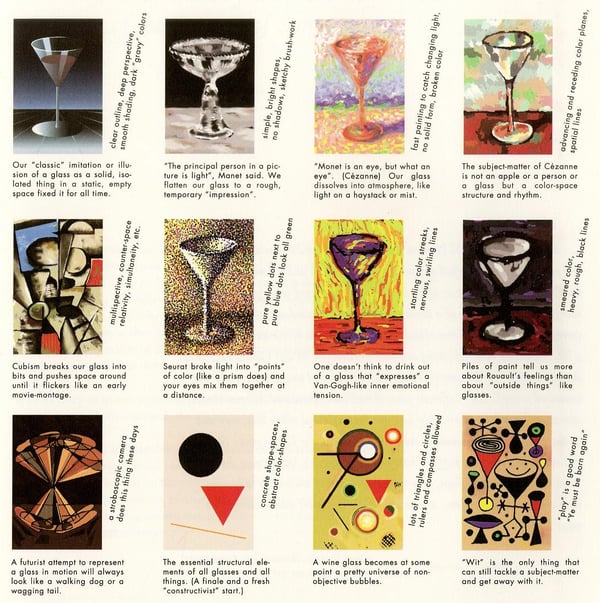

"How to Look at Things through a Wine-Glass," Edward Tufte, 1997, based on a 1946 cartoon by Ad Reinhardt.

"How to Look at Things through a Wine-Glass," Edward Tufte, 1997, based on a 1946 cartoon by Ad Reinhardt.

Tufte argues that chart junk or any visual elements that do not communicate specific information are superfluous and should be omitted. He further discourages the use of decorative elements in an infographic.

Tufte also developed the data-ink ratio, which is a measurement of the amount of information communicated in a graphic as it relates to the total number of visual elements.

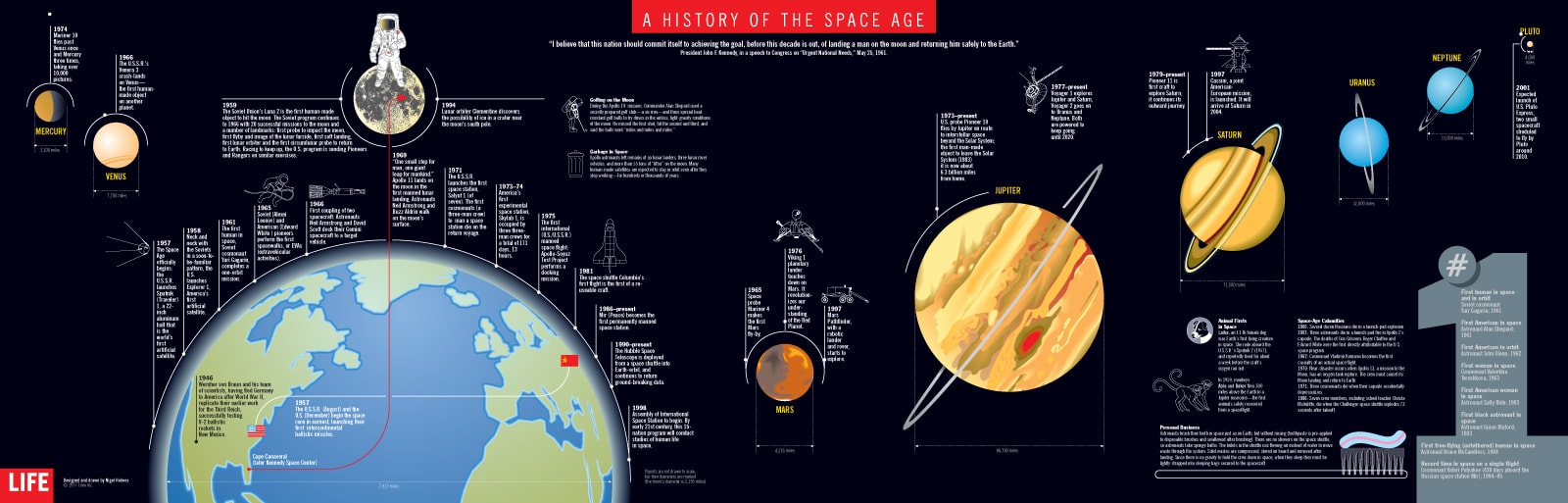

British graphic designer Nigel Holmes' work was the complete opposite of Tufte's approach. He supported the heavy use of illustration and decoration to embellish information.

A History of the Space Age

A History of the Space Age

Peter Sullivan, a British graphic designer who made infographics for The Sunday Times for almost three decades, wrote the book Newspaper Graphics, which remains one of the few books dealing with information graphics in newspapers. In 1993, he continued on the topic in his book Information Graphics in Colour.

From the 1990s onwards, the term infographic and information graphics are often used interchangeably.

According to Infographics: The Power of Visual Storytelling, the infographic of modern times uses visual cues to communicate information. The authors further wrote that an infographic doesn't have to contain a certain amount of data, present a certain level of analysis, or possess a certain complexity.

Here's an excerpt from the book:

"Put simply; there is no threshold at which something "becomes" an infographic. An infographic can range from a simple road sign of a man with a shovel that lets you know there is construction ahead, or as complex as a visual analysis of the global economy."

With that said, infographics are some of the most versatile pieces of content out there. Educators use them every day, employees use them for business reports, and marketers create infographics for lead generation. Here are some of the applications of infographics in the world today.

With the tremendous amount of information and content created every day today, getting the attention (and keeping them!) of viewers is a challenge. Using infographics for data science visualization helps address this challenge.

Aside from the appeal of visuals in capturing the audience's attention, infographics also aids in the retention and comprehension of the information presented. Data visualization formats such as pie charts, line charts, and bar graphs are also used within an infographic in presenting trends and patterns.

Next to graphs and charts, maps are also another subset of infographic use today. They are often ideal for geographical information or political data. The most popular is the choropleth map, where areas in the map are shaded with colors. A color scale is often assigned to a specific numerical or categorical data. Cartograms, proportional symbol maps, pinpoint maps, connection maps, and subway maps are other types of maps in an infographic style.

Engaging visuals can help transform marketing materials and business information to infographics that can help boost employee productivity, streamline processes, and potentially lead to skyrocketing sales or conversions.

From training new employees with complex written manuals to showcasing a specific product to prospects and investors, using infographics for your business is a game-changer for brands of all sizes.

Why are infographics effective in the classroom (physical or virtual)? Research from 2015 on using visual aids like infographics in the classroom found out that it helps students in the following areas:

As people become more fluent in presenting and understanding data, it's not uncommon to see more advanced types of infographics like animated infographics (also known as gifographics) and interactive infographics.

For the authors of Infographics: The Power of Visual Storytelling, three trends will help share the future of infographics:

In sum, it looks like infographics are here to stay. However, infographic creators need to understand that high-quality, relevant infographics are often a result of original thinking and creativity.

Kai Tomboc is an experienced content designer and writer on all things healthcare, design, and SaaS. She used to be a nurse and a telemarketer in her past lives. She lives for mountain trips, lap swimming, books, and conversations over beer.

As brands compete for attention, understanding the power of graphic design has never been more...

We’ve all seen the trope on crime TV shows: a detective stares at a blurry security image and...

by Brynne Ramella

by Brynne Ramella

A few years ago, while juggling multiple roles at a startup, I found myself designing posters,...

by Harshita Tewari

by Harshita Tewari

As brands compete for attention, understanding the power of graphic design has never been more...

We’ve all seen the trope on crime TV shows: a detective stares at a blurry security image and...

by Brynne Ramella

by Brynne Ramella