July 17, 2025

by Harshita Tewari / July 17, 2025

by Harshita Tewari / July 17, 2025

When a company needs funding, whether to launch a new product, expand operations, or just stay afloat, it doesn’t just pick a financing method out of a hat.

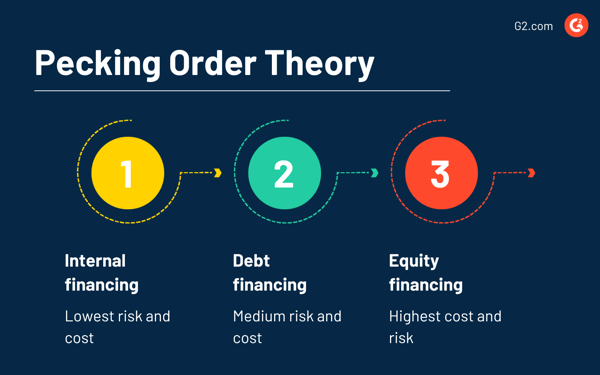

There’s a natural order to it based on a well-established theory, rather than being a preference. Known as the pecking order theory, this capital structure model explains how companies rank funding sources based on risk, cost, and how much outsiders need to know.

The pecking order theory states that firms finance projects using internal funds first, then debt, and issue equity only as a last resort. This hierarchy reduces signaling risk because issuing equity might imply overvaluation and decrease investor confidence.

Financial analysis software and financial risk management software play a significant role in how companies analyze their cash flow and financial economics to find sources of financing. Myers and Majluf popularized the pecking order theory to help businesses make sound financing decisions.

In this guide, we’ll unpack the theory, show how it works in practice, explain its roots in asymmetric information, compare it to the trade-off theory, and explore how companies use financial software to put these principles into action.

If you’re expecting a company to calculate some perfect debt-to-equity ratio and stick to it forever, that’s not how the real world works. According to the pecking order theory, most firms don’t start with an ideal capital mix. Instead, they follow a what’s available and least painful approach to funding.

Here’s how the hierarchy plays out:

Whenever possible, companies prefer to use their own profits. It’s cost-free, doesn’t involve outside parties, and keeps control in-house. There’s no debt to repay, no equity to dilute, and no financial footnotes to explain to shareholders. Retained earnings are the cleanest option, which is why it's at the top of the list.

Debt financing comes in second because of the interest payments associated with using debt capital. Whether the company takes out business loans or issues corporate bonds, it will have to pay some interest, making the cost of debt more than the non-existent cost of using retained earnings.

Still, it’s often the lesser evil compared to issuing new shares.

Equity financing (issuing new stock) is typically the last move, not because it’s logistically hard, but because of what it signals. Investors often see share issuance as a telltale sign of a higher share valuation than the market value. They treat this signal as an indicator of soon-to-drop share prices.

On top of that, equity is expensive. Investors expect higher returns to compensate for risk, and existing shareholders don’t love seeing their slice of the pie shrink. That’s why equity financing usually comes into play only when internal and debt options are maxed out, or strategically off the table.

To really get why companies stick to a financing hierarchy, you need to understand the power of information imbalance, or in more technical terms, asymmetric information. This happens when insiders (like executives) have a clearer picture of the company’s financial health, risks, and future prospects than outsiders (like lenders or investors).

Now, not all financing methods are affected equally by this information gap.

When a company uses its funds, there’s no gap. No one needs convincing. It’s the most straightforward and least risky option, because the company knows exactly what it’s working with.

Debt introduces a bit more complexity. Lenders don’t need to know everything about the company; they mostly care whether the business can pay them back, with interest. If the repayment risk is low and the financials check out, debt remains a relatively affordable option.

But things change dramatically with equity. Equity investors are putting their money in without a guaranteed return. They’re relying on limited public information and have to trust management’s outlook. Because they’re flying blind, they’ll demand higher returns to make up for the uncertainty, and that’s what drives up the cost of equity capital.

So when companies follow the pecking order, it’s not just about frugality. It’s about minimizing the cost of capital and avoiding market misunderstandings. The more uncertain the outside world is about your financial situation, the more you’ll have to pay to convince them you’re worth the risk.

Imagine you're the CFO of a mid-sized company with an exciting opportunity on the table: a new project that could fuel long-term growth. The catch? You’ll need $15,000 to get it off the ground. So, where should the money come from?

Option 1: You check the books. Good news: the company has enough retained earnings to fully cover it. That’s the ideal scenario. You don’t need to borrow from a bank, dilute ownership, or explain anything to investors. Just allocate the funds and go. Clean, simple, and zero friction.

Option 2: But let’s say retained earnings are already tied up elsewhere. Your next move? Take on debt. You approach a lender and get approved for a short-term loan at 5% interest. That’s $750 in financing cost ($15,750 in total) — not nothing, but manageable. You preserve ownership and send no red flags to the market. Of course, there’s repayment pressure now, and the loan affects your debt-to-equity ratio, but it's still a common and relatively low-cost move.

Option 3: As a CFO, you might conclude that debt financing isn’t ideal because lenders don’t have the debt capacity, or you aren’t sure your company will have enough net debt after paying the money it borrows.

You may also want to improve the company’s debt ratios. Better to catch these debt issues beforehand; you wouldn't want to go bankrupt! Now, you can use equity financing and issue equity to get that $15,000 you need.

If your company's stock price is $30 per share, you'd need to sell 500 shares to gain $15,000 in debt capital. However, this decreases your share price by, let's say, $2 per share, making each share worth $28. That means you're giving up an extra $2 per share (or $1,000 total) when you sell those 500 shares.

You would get the $15,000 right away, but end up paying more dividends ($16,000 in total) when factoring in the cost of new equity.

Not every company follows the same logic when deciding how to finance growth, and that’s where the trade-off theory enters the discussion.

While the pecking order theory explains how companies tend to behave (based on access to information and signaling concerns), the trade-off theory is more of a prescriptive model. It says a company should aim for an optimal capital structure: balancing the benefits of debt (like tax savings) against the risks (like bankruptcy or financial distress).

So which one’s right?

Well, they’re not mutually exclusive. In fact, many businesses start by following the pecking order, and later refine their structure using trade-off theory principles once they’re mature enough to model risk and return precisely.

Here’s how the two compare:

| Factor | Pecking order theory | Trade-off theory |

| Core idea | Minimize financing friction | Optimize capital mix |

| Key driver | Asymmetric information | Balance the tax benefit of debt vs. the cost of distress |

| Behavior style | Reactive and preference-based | Strategic and target-based |

| Works best for | Startups, private firms, and uncertain markets | Mature companies with stable earnings |

| Key limitation | No “optimal” ratio, just a hierarchy | Assumes companies can quantify risk perfectly |

In simple terms, the pecking order shows how companies tend to act, while trade-off theory suggests how they should act, assuming they’ve got the data and risk tolerance to back it up.

The pecking order theory is a smart default, but not a hard rule. In some cases, flipping the script on the usual funding order can actually be the better move.

Here’s when that makes sense:

Like any financial framework, the pecking order theory isn’t flawless. Here are some of its advantages and disadvantages.

Here’s where the pecking order theory provides clear strategic value for finance teams and decision-makers.

For all its clarity, the model misses some important nuances that matter in modern finance.

The pecking order theory can only be used when you understand a company's finances. Gathering and analyzing financial data can be stressful without the right tool. G2 helps companies find financial analysis and risk management solutions to track, manage, and analyze finances.

Financial analysis tools help companies monitor financial performance. These solutions gather and analyze financial transactions and accounting data to help you stay on top of key performance indicators (KPIs) and make wise financial decisions. Accountants also use these systems for report generation and financial compliance purposes.

Financial risk management systems aid financial services institutions in spotting and mitigating investment risks. These tools play a key role in how companies simulate investment scenarios, conduct in-depth analyses, and find suitable investment opportunities.

Got more questions? We have the answers.

It assumes companies prefer to fund themselves using internal cash first, then debt, and only turn to equity as a last resort. The model reflects how businesses rank funding sources based on cost, control, and risk.

Because it creates risk for investors, when outsiders know less than company insiders, they demand a higher return, especially for equity. That’s what makes external capital more expensive.

Absolutely, particularly for startups, private firms, and companies in uncertain markets. It’s often used alongside other models like trade-off theory or market timing theory to form a more complete funding strategy.

Pecking order is about behavioral preference: internal funds first, equity last. Trade-off theory is more quantitative, aiming for the ideal debt-equity mix by balancing tax advantages with bankruptcy risk.

Yes, but often in reverse. Startups usually lack internal funds or credit history, so they raise equity first, typically through angels or VCs, not because it’s ideal, but because it’s accessible.

The pecking order theory explains how and why companies choose between internal financing, debt, and equity to finance their businesses. The theory doesn’t guide decision-making despite its usefulness in financial management based on capital structure decisions.

Plus, there’s no quantitative metric that shows you how to analyze or calculate financing sources. Consider using the pecking order theory with other tools to drive sound capital market decisions.

Leverage best-in-breed financial predictive analytics software solutions to drive investment strategy with historical data analysis.

This article was originally published in 2019. It has been updated with new information.

Harshita is a Content Marketing Specialist at G2. She holds a Master’s degree in Biotechnology and has worked in the sales and marketing sector for food tech and travel startups. Currently, she specializes in writing content for the ERP persona, covering topics like energy management, IP management, process ERP, and vendor management. In her free time, she can be found snuggled up with her pets, writing poetry, or in the middle of a Netflix binge.

You walk into your office Monday morning and spy a colleague enjoying a powdered donut.

by Maddie Rehayem

by Maddie Rehayem

If you’ve ever felt stuck choosing between the safety of bonds and the growth potential of...

by Soundarya Jayaraman

by Soundarya Jayaraman

Communication is related to every human activity.

by Mary Clare Novak

by Mary Clare Novak

You walk into your office Monday morning and spy a colleague enjoying a powdered donut.

by Maddie Rehayem

by Maddie Rehayem

If you’ve ever felt stuck choosing between the safety of bonds and the growth potential of...

by Soundarya Jayaraman

by Soundarya Jayaraman